Le colostrum est la base de la santé du veau. Il fournit au veau nouveau-né des immunoglobulines par le biais de transfert passif qui sont essentiels à la survie, à la résistance aux maladies et aux performances à long terme. Des décennies de recherche ont montré que les veaux présentant des niveaux élevés d'immunité passive ont moins de risques de morbidité et de mortalité, une meilleure croissance et une meilleure productivité tout au long de leur vie. Par conséquent, la plupart des producteurs laitiers sont bien conscients de l'importance de donner du colostrum rapidement et en quantité suffisante après la naissance.

Malgré cette prise de conscience, il reste difficile d'obtenir des résultats cohérents en matière d'immunité passive dans de nombreuses exploitations. Même les troupeaux dotés de solides programmes de gestion du colostrum continuent d'observer une variabilité des concentrations sériques d'immunoglobulines G (IgG) entre les veaux. Cette incohérence est souvent frustrante, en particulier lorsque les meilleures pratiques recommandées en matière de calendrier et de volume sont respectées.

L'une des principales raisons de ce défi est que le colostrum maternel lui-même est très variable. La qualité du colostrum peut varier considérablement d'une vache à l'autre, d'un vêlage à l'autre au sein d'une même vache et même au sein d'un même troupeau le même jour. Une grande partie de cette variabilité est due à des facteurs biologiques et physiologiques qu'il est difficile, voire impossible, de contrôler totalement. Par conséquent, se fier uniquement au colostrum maternel sans stratégie de gestion de cette variabilité peut exposer les veaux à un risque plus élevé d'échec du transfert de l'immunité passive.

Qu'est-ce qui détermine la qualité du colostrum ?

La qualité du colostrum est le plus souvent définie par sa concentration en IgG, l'IgG étant le principal anticorps responsable de l'immunité passive chez le veau nouveau-né. Bien que le volume, la propreté et la charge bactérienne du colostrum soient également importants, la concentration en IgG reste le facteur déterminant de la quantité d'immunité qu'un veau absorbe en fin de compte.

La concentration d'IgG dans le colostrum est influencée par un large éventail de facteurs biologiques et de gestion, notamment la parité, la gestion des vaches taries et le moment de la collecte du colostrum.

Parité. La parité est l'un des facteurs les plus constants de la qualité du colostrum. Les vaches multipares produisent non seulement un plus grand volume de colostrum, mais leur colostrum contient généralement des concentrations plus élevées d'IgG et de protéines totales et des concentrations plus faibles de matières grasses par rapport à celui des génisses primipares.

Parité. La parité est l'un des facteurs les plus constants de la qualité du colostrum. Les vaches multipares produisent non seulement un plus grand volume de colostrum, mais leur colostrum contient généralement des concentrations plus élevées d'IgG et de protéines totales et des concentrations plus faibles de matières grasses par rapport à celui des génisses primipares.

Gestion des vaches taries. De courtes périodes de sécheresse, généralement définies comme étant inférieures à 47 à 51 jours, ont été associées à une réduction du volume du colostrum, probablement en raison d'une altération de la croissance des cellules mammaires ou de la fonction de la glande mammaire pendant la formation du colostrum. La nutrition prépartum, en particulier l'équilibre énergétique et l'état des micronutriments, peut également influencer la fonction immunitaire et la synthèse du colostrum. Les facteurs de stress environnementaux, tels que le stress thermique en fin de gestation, ont également été associés à une diminution de la qualité du colostrum.

Moment de la collecte du colostrum. Les concentrations d'immunoglobulines diminuent rapidement après le vêlage lorsque le colostrum passe au lait mature. Un retard dans la première traite, même de quelques heures seulement, peut réduire considérablement la concentration en IgG. En fait, la concentration d'IgG dans le colostrum diminue de ~4% pour chaque heure de retard dans la collecte après le vêlage.

Nombre de ces facteurs interagissent et varient d'une vache à l'autre. Même dans le cadre d'une excellente gestion, il n'est pas réaliste de s'attendre à une qualité uniforme du colostrum pour tous les vêlages. C'est la raison pour laquelle le colostrum doit être de bonne qualité. la variabilité n'est pas le reflet d'une mauvaise gestion, mais plutôt le reflet d'une mauvaise gestion. une réalité biologique de la production de colostrum.

Quelle est la variabilité du colostrum maternel ?

La variabilité de la qualité du colostrum observée dans les troupeaux laitiers commerciaux est considérable. Dans une étude réalisée en 2019, le Dr Sandra Godden de l'université du Minnesota a défini un colostrum de haute qualité comme contenant plus de 50 g d'IgG par litre. En utilisant cette norme, de multiples études ont montré qu'une proportion considérable de colostrum n'atteint pas ce seuil. Une vaste étude américaine portant sur 104 exploitations laitières réparties dans 13 États a révélé que 23% des échantillons de colostrum étaient classés comme étant de mauvaise qualité (contenant moins de 50 g d'IgG/L). Des résultats similaires ont été rapportés dans une étude portant sur 18 exploitations laitières de l'État de New York, où entre 20 et 24% d'échantillons de colostrum ont été considérés comme étant de mauvaise qualité, en fonction de la parité des vaches.

D'autres systèmes de production présentent une variabilité encore plus grande. Dans une étude portant sur 21 exploitations laitières en pâturage en Irlande, 44% des échantillons de colostrum contenaient moins de 50 g d'IgG/L, ce qui met en évidence les difficultés rencontrées pour obtenir un colostrum de haute qualité dans les systèmes de pâturage. Les données canadiennes montrent une variabilité comparable. Une étude menée au Québec a recueilli des échantillons de colostrum auprès de 51 troupeaux laitiers et a révélé que la concentration moyenne d'IgG se situait juste au-dessus du seuil couramment utilisé de 56 g/L. La distribution était toutefois large, avec des échantillons de colostrum de plus de 50 g/L. Cependant, la distribution était large, avec des concentrations d'IgG allant d'environ 21 g/L à 97 g/L. Dans l'ensemble, ces résultats suggèrent que ¼ à 1/5 des colostrums distribués peuvent être inférieurs aux normes de qualité recommandées.

Cette variabilité signifie que deux veaux nourris avec le même volume de colostrum au même moment après la naissance peuvent recevoir des quantités d'IgG très différentes. Concrètement, un veau nourri avec quatre litres de colostrum de haute qualité peut recevoir plus du double de la masse d'IgG par rapport à un veau nourri avec le même volume de colostrum de mauvaise qualité. Du point de vue du veau, il s'agit de points de départ biologiques totalement différents.

Évaluation de la qualité du colostrum

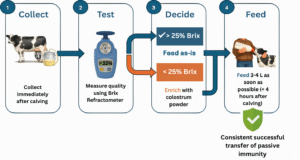

Compte tenu de la variabilité inhérente à la qualité du colostrum maternel, l'évaluation du colostrum avant l'alimentation est une étape importante dans la réduction des risques pour le veau nouveau-né. L'évaluation à la ferme est le plus souvent réalisée à l'aide d'un réfractomètre Brix. Il a été démontré que le pourcentage Brix est en corrélation avec la concentration d'IgG dans le colostrum et qu'il constitue un outil rapide et pratique permettant de prendre des décisions en temps réel.

En utilisant un seuil de 22% Brix ou plus, il y a un haut niveau de confiance que le colostrum est de haute qualité. Plus précisément, les docteurs Buczinski et Vandeweerd ont déterminé que le colostrum mesurant au moins 22% Brix avait une probabilité de 94% de contenir plus de 50 g d'IgG/L en 2016. Le colostrum atteignant ou dépassant ce seuil convient généralement pour les premières tétées, tandis que des valeurs inférieures indiquent un risque plus élevé de livraison inadéquate d'IgG au veau.

Lorsqu'il est utilisé de manière cohérente, le test Brix permet au personnel de l'exploitation de distinguer le colostrum de qualité supérieure de celui de qualité inférieure et de prendre des décisions éclairées sur la manière dont le colostrum doit être réparti. Cette approche permet une distribution plus cohérente des IgG aux veaux et jette les bases de protocoles normalisés de gestion du colostrum.

Que peut-on faire avec un colostrum de mauvaise qualité ?

Lorsque la qualité du colostrum est évaluée, une partie du colostrum est inférieure aux seuils recommandés. L'élimination du colostrum de mauvaise qualité est souvent peu pratique, en particulier dans les troupeaux comptant une forte proportion de génisses primipares ou pendant les périodes de stress environnemental. Par conséquent, les producteurs doivent décider de la meilleure façon de gérer le colostrum qui ne répond pas aux objectifs de qualité tout en protégeant la santé des veaux.

L'enrichissement du colostrum offre une solution pratique. L'enrichissement consiste à compléter le colostrum maternel de mauvaise qualité par un substitut de colostrum afin d'augmenter la masse totale d'IgG délivrée au veau. Cette approche permet aux producteurs de maximiser leur propre colostrum en conservant les composants bioactifs plus larges du colostrum maternel tout en réduisant le risque associé à une faible concentration d'IgG.

L'utilité de cette stratégie a été démontrée par le Dr Lopez à l'Université de Guelph en 2023. Dans cette étude, l'enrichissement du colostrum maternel de faible qualité de 30 g d'IgG/L à 60 g d'IgG/L a entraîné une augmentation des concentrations sériques d'IgG, de 12 g/L à 20 g/L. Ce qui est sans doute le plus important, c'est qu'ils ont observé le transfert de l'immunité passive en cas d'échec est passé de 19% à 0%. Lorsque le colostrum maternel contenant 60 g d'IgG/L a été enrichi à 90 g d'IgG/L, des augmentations plus faibles des IgG sériques ont été observées. Cependant, l'enrichissement a permis d'augmenter la proportion de veaux présentant une excellente immunité passive, définie par des concentrations d'IgG sériques supérieures à 25 g/L, de 50% à 62% par rapport aux veaux nourris uniquement avec le colostrum maternel dosé à 60 g d'IgG/L.

Ensemble, le test du colostrum et l'enrichissement ciblé constituent une voie pratique vers une gestion standardisée du colostrum et des résultats plus prévisibles en matière de santé des veaux.

La mise en place d'unTous ensemble

Pris ensemble,

ces principes soutiennent une approche simple, basée sur la décision, de la gestion du colostrum qui réduit la variabilité et améliore la cohérence sans investissement dans l'infrastructure ni augmentation importante de la demande de main-d'œuvre.

Messages à emporter

La qualité du colostrum est intrinsèquement variable, même dans les troupeaux bien gérés, et la concentration en IgG est le principal facteur de l'immunité passive. Il est important de donner du colostrum rapidement et en quantité suffisante, mais cela ne permet pas de remédier à la mauvaise qualité du colostrum, qui se produit dans une proportion substantielle des tétées. L'évaluation de la qualité du colostrum à l'aide d'un réfractomètre Brix et l'enrichissement du colostrum de mauvaise qualité constituent une approche pratique et standardisée pour réduire la variabilité et fournir une immunité passive plus cohérente entre les veaux.

Écrit par Dr. Dave Renaud

Épidémiologiste vétérinaire, Université de Guelph